Introduction

Child and adolescent mental health services in Uganda have vastly improved over the last decade and ACT International has played a part in this change, training more than 160 health and social care professionals to deliver a child-centred treatment for trauma - Child Accelerated Trauma Technique (CATT). There are now CATT counsellors in every region of the country helping trafficked children, children suffering from domestic violence and abuse and those who've fled conflict in neighbouring countries.

The aim of this report is to assess the impact of ACT International's work in Uganda, focussing on the clinical benefits of CATT in treating symptoms of PTSD and the challenges of implementing CATT on the ground.

An overview of child and adolescent mental health services in Uganda

Over half of Uganda's population are under 15 years old and many have been subjected to traumatic events leading to a high rate of mental health disorders. The country's history of prolonged armed conflicts such as the war involving the Lord's Resistance Army, has left a legacy of children who grew up in a brutalised environment without their parents and who face discrimination and social stigma. Uganda's open-door policy has swelled the number of orphans bringing almost one and a half million refugees from countries like Sudan, Rwanda, Burundi, Ethiopia, Somalia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. According to the Ugandan Government, the burden of mental and neurological disorders has been increased "by the effects of war, exposure to violence including defilement, poverty, physical, emotional and sexual abuse, commercial sex and sex for survival, addiction to substances such as alcohol and cannabis, infection or being affected by HIV/AIDS and other disease like malaria resulting in psychological and/or intellectual handicap, bereavement and separation." Depression among secondary school students and anxiety disorders, particularly among girls, are high.

“Child abuse is so common… We are raised by parents who are punitive and they think it's a normal thing to beat a child. And then Uganda being a chaotic country sometimes, most especially around election periods, people being whisked away, tortured, children exposed to so much in the neighbourhood. And then the domestic violence and then the accidents as well...So there are so many traumatic instances here. Then we have another problem of refugees.” —James Nyereko, Principal Clinical Psychologist, Butabika National Referral Hospital.

When ACT International (then Luna Children's Charity) began to work in Uganda in 2011, child and adolescent mental health services were inaccessible to most Ugandans and there was only one psychiatrist specialising in child and adolescent mental health. From 2012, ACT International worked as a partner of East London NHS Foundation Trust on its mental health link with Butabika National Referral Hospital in Kampala, training the country's first children's mental health specialists. Dr Godfrey Zaari Rukundo, one of the first to be trained in CATT, was among those who persuaded the Ministry of Health to support the two-year children's mental health diploma course, accredited by Mbarara University of Science and Technology where he is Head of the Department of Psychiatry. CATT was an important element of the course within the module on childhood trauma.

“With an adult you could easily do something. You could easily ask them to say what happened, and maybe you have a conversation but, because children were not able to express themselves most of the time following trauma, it was quite challenging to handle children who were traumatised. We just ended up giving them medication without knowing what we are treating. So when CATT came, it was very helpful because at least it can be used with a range of children, whether they were able to communicate, whether they are willing to talk about their trauma or not, at least as long as they're able to understand the instructions, you could do it.” —Dr Godfrey Zaari Rukundo, Head of Psychiatry at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital and Senior Lecturer at Mbarara University of Science and Technology.

Although CATT training is specifically designed to help children suffering from PTSD, a social impact assessment carried out in 2016 showed that it increased counsellors' psycho-social knowledge, improved their understanding of children's rights and promoted child-centred practice. Since then, more than 160 CATT counsellors have been trained, and 14 have themselves become trainers, spreading practice across the country.

In 2017, the Ugandan Ministry of Health set out ambitious policy guidelines for child and adolescent mental health;but the recent pandemic offers a stark reminder that there is still much to be done. School closures, social distancing, curfews, and lockdown led to an upsurge in domestic violence, child abuse, teenage pregnancies and suicide yet, far from throwing more resources into mental health, administrators did the opposite. In most of the country's regional referral hospitals, wards for psychiatric patients were turned into COVID wards, and psychiatric patients could not access services.

“They quickly thought that the mental health units should be the places for COVID treatment. So most regional referral hospitals actually sent out our patients and replaced them with COVID patients. They thought that they are not as important as maybe surgical patients. They couldn't think of others, maybe even of ophthalmology, but they thought of psychiatry.” —Dr Godfrey Zaari Rukundo

In most cases, the service is now back to a pre-pandemic norm but there are still major gaps which reduce a child or young person's chances of recovery. Child and adolescent services (CAMHS) are not integrated into primary health care, hospitals and clinics remain underfunded and understaffed, and mental health remains low on a list of priorities competing for limited funds with more obvious killer diseases such as malaria and HIV/AIDS. An additional problem is the lack of public awareness and the stigma attached to mental ill health. If parents do seek help, it tends to be traditional healers to whom they turn.

Methodology

In May 2022, Uganda's first two-day conference for CATT counsellors took place at Butabika National Referral Hospital. Of the 38 practitioners who attended, 26 (seven women and 19 men) filled in a questionnaire about their practice, representing almost half the country's practising CATT counsellors. They were first trained in CATT between 2012 and 2022. Respondents were asked to describe their professional role or job title. They fall broadly into two categories: 15 are specialists who have a degree level qualification which entitles them to work as clinical psychologists, psychiatric clinical officers (PCOs), psychosocial counsellors and psychiatric nurses. There are 11 non-specialists who work with children, for instance as general nurses or therapists, social workers and teachers.

| Job title | Number | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| Non-specialist | 11 | 42% |

| Nurse | 4 | 15% |

| Child development worker | 1 | 4% |

| Nursing officer | 1 | 4% |

| Occupational therapist | 1 | 4% |

| Psychosocial counsellor | 1 | 4% |

| Social worker | 1 | 4% |

| Teacher | 1 | 4% |

| Therapist | 1 | 4% |

| Specialist | 15 | 58% |

| PCO | 4 | 15% |

| PCO (CAMHS) | 2 | 8% |

| Clinical psychologist | 2 | 8% |

| Psychiatric nurse | 2 | 8% |

| CPO (CAMHS) | 1 | 4% |

| Principal clinical psychologist | 1 | 4% |

| Principal PCO | 1 | 4% |

| Principal PCO (CAMHS) | 1 | 4% |

| Psychologist | 1 | 4% |

| Total | 26 | 100% |

Respondents were first trained in CATT between 2012 and 2021 and now work in a variety of settings. 62% work in regional referral hospitals, others work for humanitarian organisations in refugee camps, schools, or centres for disadvantaged children. Most practise CATT as part of their official duties while others have chosen to do so on a voluntary basis.

Fourteen counsellors, including two who were not among the respondents, were subsequently interviewed. The researcher was also given access to case records from counsellors working for CRESS UK on the South Sudanese border. She interviewed four children in Kisubi and Lira who have been treated with CATT for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well as their counsellor and carers. This report summarises the findings of that research. Authored by a trustee of ACT International, it cannot be regarded as an independent survey but is presented in the hope that, together with partner organisations, ACT International can draw on the Ugandan experience to evaluate and improve our training and the practice of CATT worldwide.

Children's Accelerated Trauma Technique

CATT enables children to reprocess traumatic memories through imaginative play, combining play and arts therapy with trauma focussed cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and children's rights principles. There are 12 stages which include finding a safe and comfortable setting for the child, carrying out an assessment of basic needs and working with the child to set measurable and realistic goals. Symptoms of PTSD are measured before and after therapy.

In the memory processing phase of CATT, children are asked to compile a list of characters involved in the traumatic events and to choose a safe place for the beginning and end of the narrative. They then create those characters out of available materials and use them to enact the story. After reaching the end, they are asked to re-tell the story backwards, a process which uses working memory. The therapist asks them to repeat this forward and backward narrative until the emotional response is reduced or eliminated.

This is followed by a second phase of treatment in which the child tells a new story which re-frames the experience and provides it with a new, more positive meaning which is empowering and more easily recalled.

Rate of referrals

For qualified psychologists working in a medical setting, CATT is one of many treatments they may offer to children and adolescents in their care whereas, for non-specialists in the community, it may be the only psychological therapy they ever use. Asked how many children were referred to them in a typical year, answers vary widely from zero to 62, with half of all respondents (50%) estimating five or fewer referrals in a year. Those who provided higher numbers may have been answering in terms of the numbers referred to their place of work. The age range of young people referred was between 5 and 22 years old with girls and young women representing a slightly higher proportion than males.

| In a typical year how many children were referred to you for CATT counselling? | Number referred | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| 0 to 5 | 13 | 50% |

| 6 to 10 | 2 | 8% |

| 11 to 15 | 4 | 15% |

| 16 to 20 | 1 | 4% |

| 21 to 25 | 1 | 4% |

| 26 to 30 | 1 | 4% |

| 30+ | 4 | 15% |

When interviewed, some counsellors working in refugee camps reported being overwhelmed by the number of children suffering from PTSD.

“Refugee camps like Oruchinga in south western, Uganda, are overwhelmed by the numbers from DRC, because there is fighting. And now there are many buses, many lorries transporting people to the camp and CATT counsellors are overwhelmed by their numbers and they need to provide the basics. For example, right now when the refugees arrive, they are interested in the basic needs, like food, like shelter, like medical care. And therefore that is their attention. And maybe with time, they start screening for children who need CATT, but it would've taken some time and suffering doesn't wait. Meanwhile, they'll be suffering.”—Elias Byaruhanga, CATT co-ordinator in Uganda

“The organisation did not have a proper understanding about mental health, but me being a technical person in that line, I tried to guide in a way of helping. So I was the psychosocial officer working with other four assistants, but we were not enough. We were overwhelmed with the work that we were doing” —Jimmy N

While some were unable to deal with the number of cases presented, others wished more children were brought to them for treatment. One reason for a comparatively low rate of referrals was stigma or a lack of a public awareness about mental illness and available treatments. Counsellors reported that symptoms in children tended to be misinterpreted as bad behaviour punishable by beating and those parents who sought help often turned to traditional healers or expected to be given medicine with quick results rather than a more time-consuming course of therapy. As one respondent put it, "Some family members do not believe talking is treating".

“It is true that parents may not easily refer the child to a psychiatrist or a psychologist because they may not know that this is something that requires a hospital. In fact, in our African setting, we have been abused a lot. And we think that like beating the children is what will shape, sharpen them. So most of the children are beaten by the time they come to hospital, they have been beaten and brutalised by everybody. The big brother beats, the mother beats, the father beats the teachers beat... So, many times it's difficult to know that the child has a problem.” —Dr Godfrey Zaari Rukundo

“Some causes of trauma come with shame, feelings of guilt, people don't want to bring it out ... If a girl child has been sexually defiled, they'll take this child for medical examination. And, if they have a tear, they will treat that. If they have an STD, they will treat that. And it ends there. Not knowing that there is something which is still not known, which has not come out clearly. So I can't really say that there are no cases; the cases could be there, but they're silent in the community.” —Martha

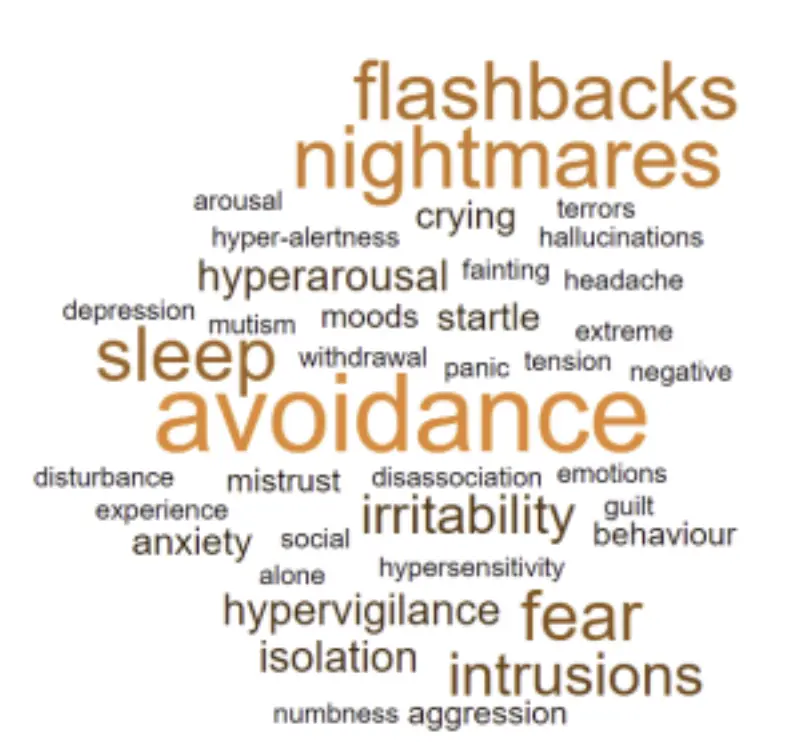

Symptoms of PTSD

Asked what symptoms of PTSD their clients presented, the most frequently mentioned in the questionnaire was "avoidance" (used 16 times across 26 questionnaires), meaning that children avoided places and people that brought back memories of the traumatic event. Other words that cropped up often were "nightmares" (10) and "flashbacks" (11) and disturbed "sleep" (10). Counsellors also described hyper arousal, negative moods, aggression, a fear of being alone, startled reactions to stimuli, a loss of interest in things they once loved and excessive worries.

Measuring the effectiveness of CATT

Respondents reported having between four and 11 sessions with a child to complete CATT, with the average being 6.8.

| What is the average number of sessions you have with a child to complete CATT? | Number of responses | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 4 | 16% |

| 5 | 3 | 12% |

| 6 | 5 | 20% |

| 7 | 3 | 12% |

| 8 | 4 | 16% |

| 9 | 4 | 16% |

| 10 | 1 | 4% |

| 11 | 1 | 4% |

| Total | 25 |

As a measure of CATT's effectiveness, counsellors use the Children's Revised Impact of Event Scale, CRIES-8, devised by the Children and War Foundation to screen children at risk of PTSD. Records of cases kept by the CRESS team of nine volunteer counsellors working with refugees from South Sudan show a remarkably high success rate with reduced symptoms of PTSD in 858 cases between November 2019 and December 2021.

Similarly, eight case histories recorded by Sister Florence Achulo-Osara, director of the Bishop Asili Counselling, Rehabilitation and Community Centre in Lira, show impressive reduction in the CRIES- 8 score post CATT. Four of the children referred to her for CATT therapy took part in this research, along with parents or carers. When asked if they could remember how they felt before the therapy and shown a chart of emoji faces with a scale of emotions from sad to happy, three pointed to 0 and one child pointed to 2 at the bottom of the scale. Asked to show how they felt now, they all pointed to 10 on the scale - the happiest face. As well as having their traumatic symptoms reduced, they all talked about the new opportunities they had been given as a result of Sister Florence's intervention.

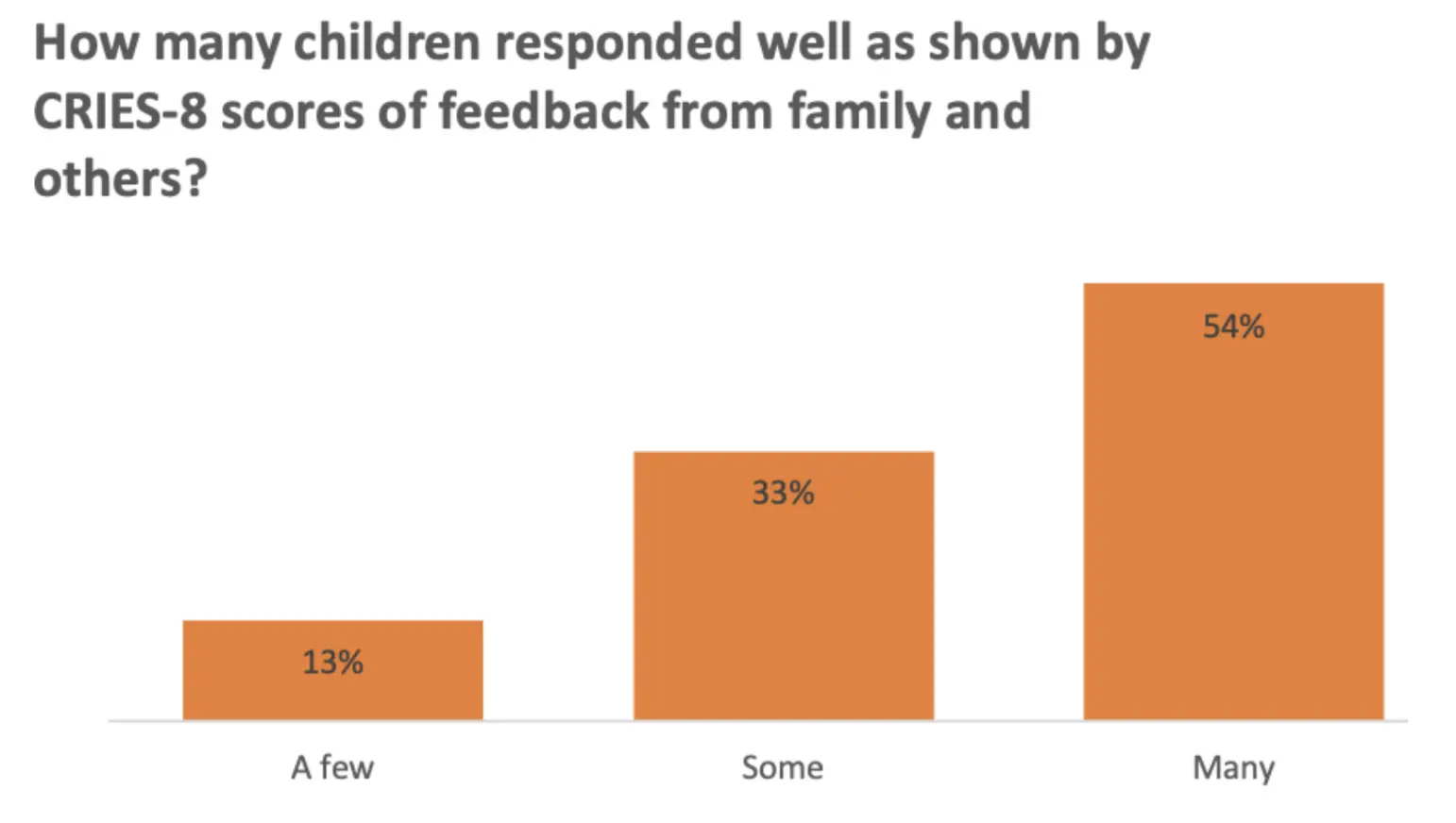

The questionnaire presents a more nuanced picture of outcomes. Counsellors were asked how many children responded well to CATT, as shown by CRIES-8 scores or feedback from family and others. Given a scale of answers from "a few" to "some" and "many", a little over half of respondents reported that many children responded well.

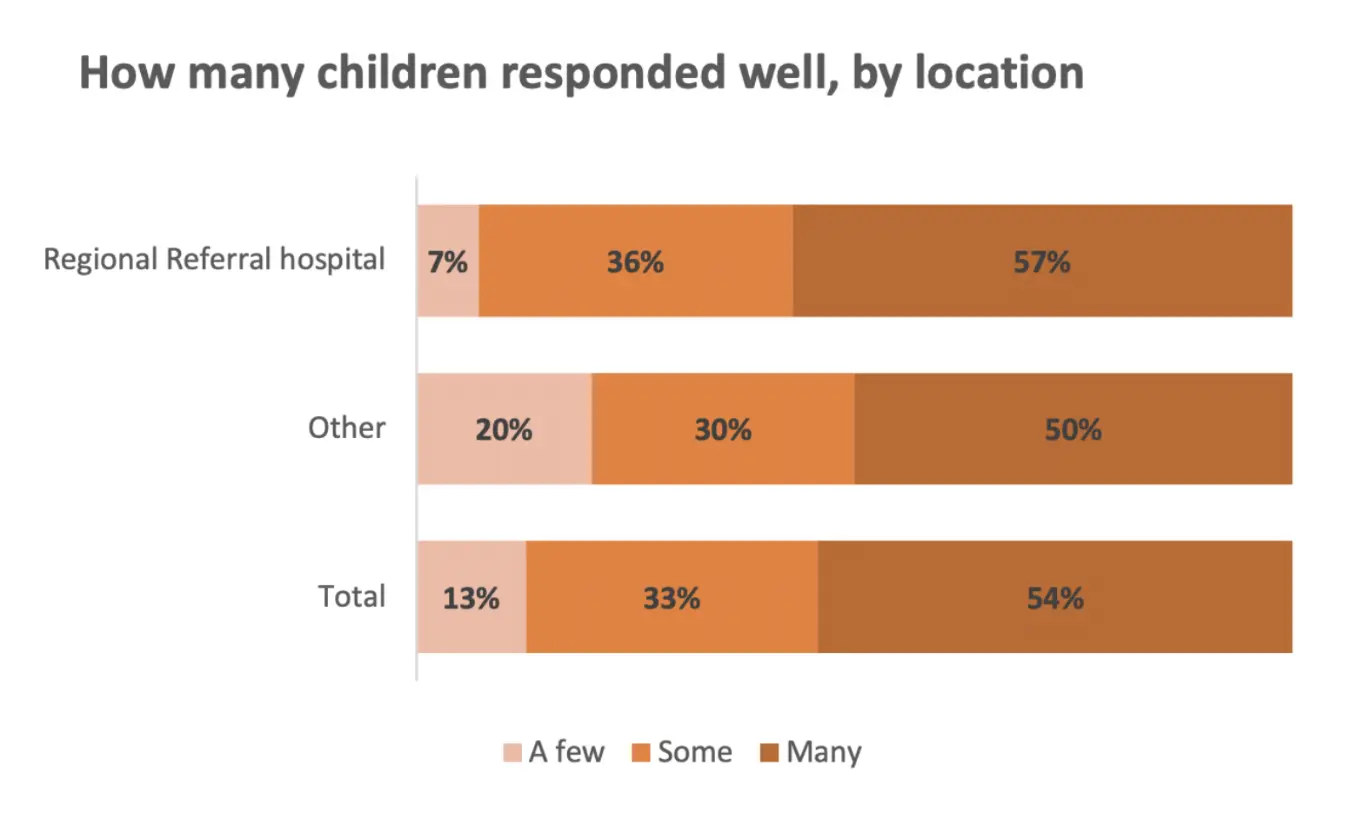

Although the sample size is too small to infer significant differences, results to this question did vary somewhat based on other variables. A slightly higher proportion of respondents based in regional referral hospitals gave more positive assessments than those based in other predominately non-clinical or refugee settings, with 93% reporting some or many positive responses compared to 80% for other locations.

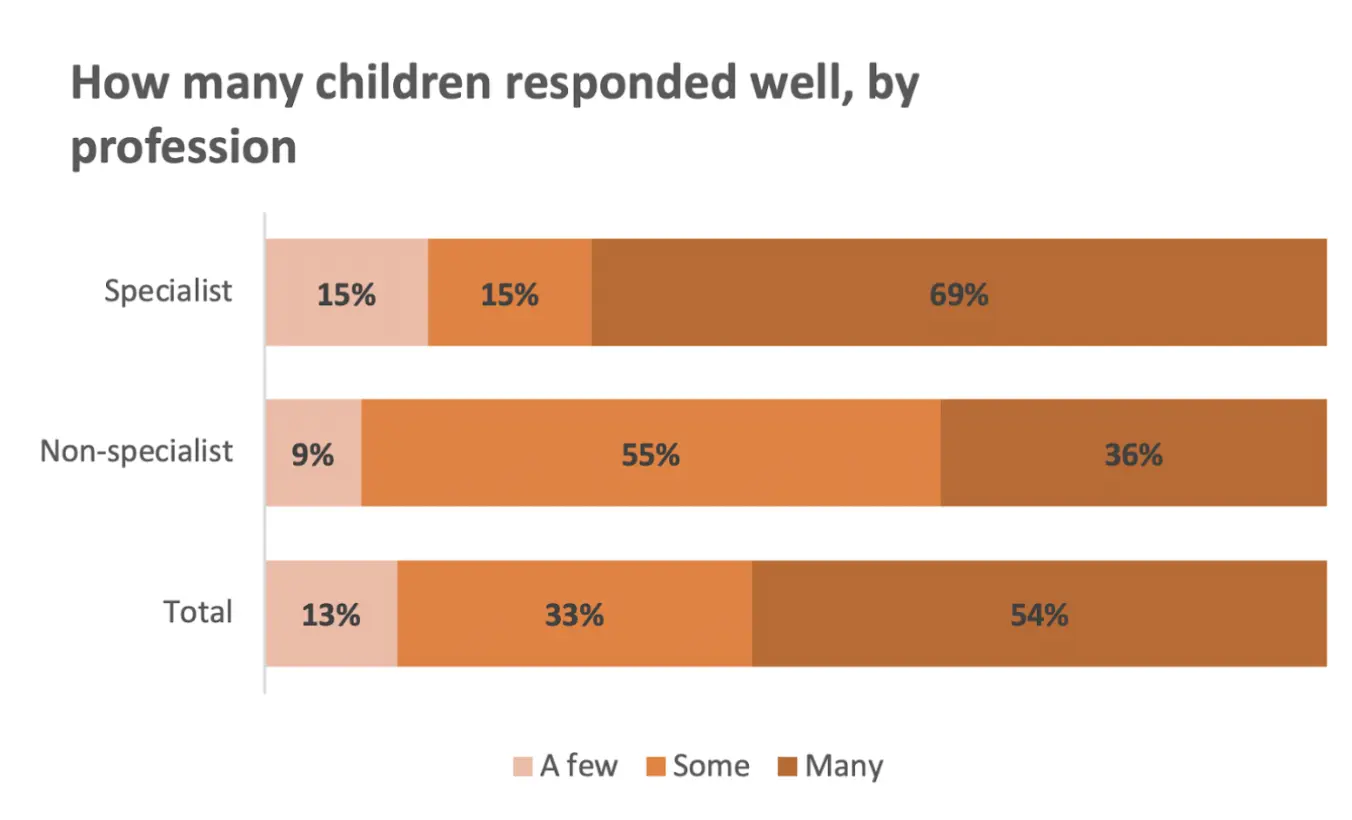

Results to the same question based on respondents' job title also varied, although less clearly. Paradoxically, while those in specialist roles were more likely to say that "many" children responded well (69% compared to 36% for non-specialists), specialists were more likely than non-specialists to report that "few" children responded well (15% compared to 9%).

A detailed account of individual workplaces and systems throws some light on these variations. For instance, counsellors working in regional referral hospitals tend to be more highly qualified and better supported in terms of supervision and peer support, which may attribute for a higher success rate. Many of the counsellors who were interviewed stressed the importance of supervision or peer support, both to improve their practice and avoid burn-out.

“You find that may be in the hospital you trained one or two people and they're at the same level and may be supervision is not enough. And again, they don't come together to share their cases, what I call peer supervision. So I don't think there's been enough, but I think that is the way to go, to encourage them where they don't have a senior person at least to do peer supervision.” —Elias B

“I miss that so much. You know, sometimes it's like feeling stuck, like, what do I do? Or you've seen a case that has really stressed you so much. And you feel like talking to somebody who understands what you are going through, but this person is not available. And I would really need somebody who can offer me support supervision.” —Martha A

Benefits of using CATT

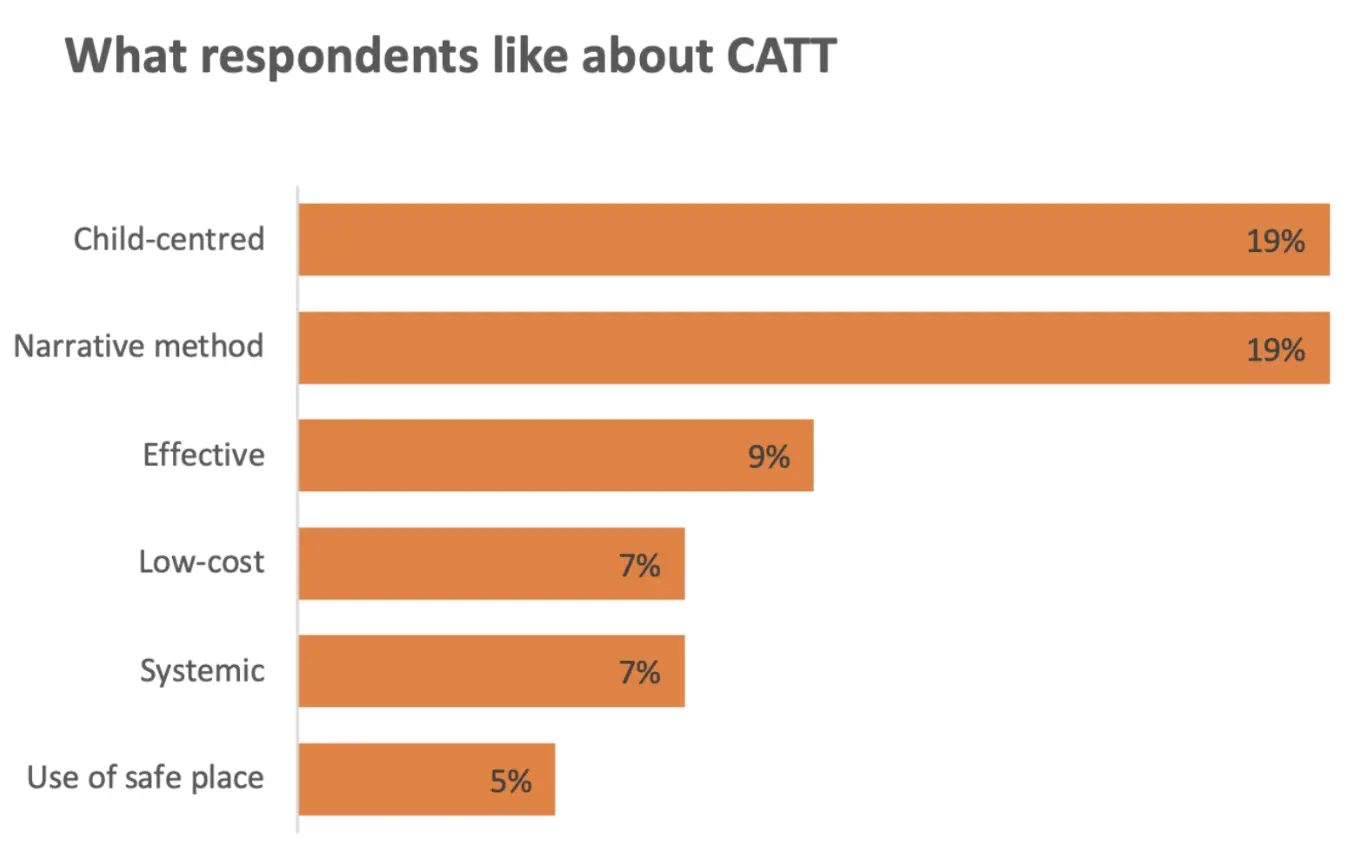

Asked what they liked about using CATT, the most frequent responses in the questionnaire related to it being child-centred (19% of responses), its narrative method (19%), and that it was effective (9%).

"CATT is cheap compared to other therapies and more interactive."

“I like CATT because when done right, it is magical.”

“Even children with limited use of language or who don't speak your language can be engaged.”

“A therapist works with the child and the systems that the child and carers have identified.”

Most counsellors reported that CATT had an impact not only on individual children but on their families, for instance by relieving symptoms of trauma, helping the child return to school, improving relationships and teaching parenting skills.

“CATT has had a great positive impact on children's family because the family comes to understand the child better and gets involved in addressing the problem.”

“Families previous dysfunctional and socially disintegrated have become functional and socially connected.”

“Children are able to work well and so it reduces burden on families.”

“Families who used not to have peace and rest due to behaviours shown by their children are able to have a big smile on their faces after successful CATT therapy.”

In addition to its therapeutic benefits, a number of counsellors said in their interview that CATT training had changed their entire working practice, highlighting the value of psychoeducation as a means of sensitising the wider community to issues of mental health and trauma. This had improved their professional standing and self-esteem.

“I realized many children and adolescents have been taking medicine when they really would not need it. That was the most thing that impacted my life. Most children are taking drugs or medicine when they can be well on psychological therapies. So I found the CATT so helpful in such a way that some adolescents and children get better without medicine, and which is helping their general health and helping their families.” —Prima S, general nurse

“My teaching has been made different ... Here we have a culture of beating children. The child does a mistake - you beat. Some were beaten and ran from school. Parents tried to bring them back. This time they run from home. So they wait on the street. I follow those children, I brought them back. Slowly by slowly. Now, by the time we ended, they had settled in class study; the head teacher will say, what is this? ... Actually, the school nurse asked me, “Which tablet did you give these children?” I said, “I'm not a doctor. I've not given them any tablet, but I have talked to them”. He said, “No, you have something special in you”. I just praised the Lord for that.” —Didas M, teacher

“My teaching has been made different ... Here we have a culture of beating children. The child does a mistake - you beat. Some were beaten and ran from school. Parents tried to bring them back. This time they run from home. So they wait on the street. I follow those children, I brought them back. Slowly by slowly. Now, by the time we ended, they had settled in class study; the head teacher will say, what is this? ... Actually, the school nurse asked me, “Which tablet did you give these children?” I said, “I'm not a doctor. I've not given them any tablet, but I have talked to them”. He said, “No, you have something special in you”. I just praised the Lord for that.” —Beatrice K

Challenges of using CATT

Respondents to the questionnaire were asked to list some of the challenges of using CATT. Again, their answers and the evidence of detailed interviews shed light on structural issues as well as individual caseloads.

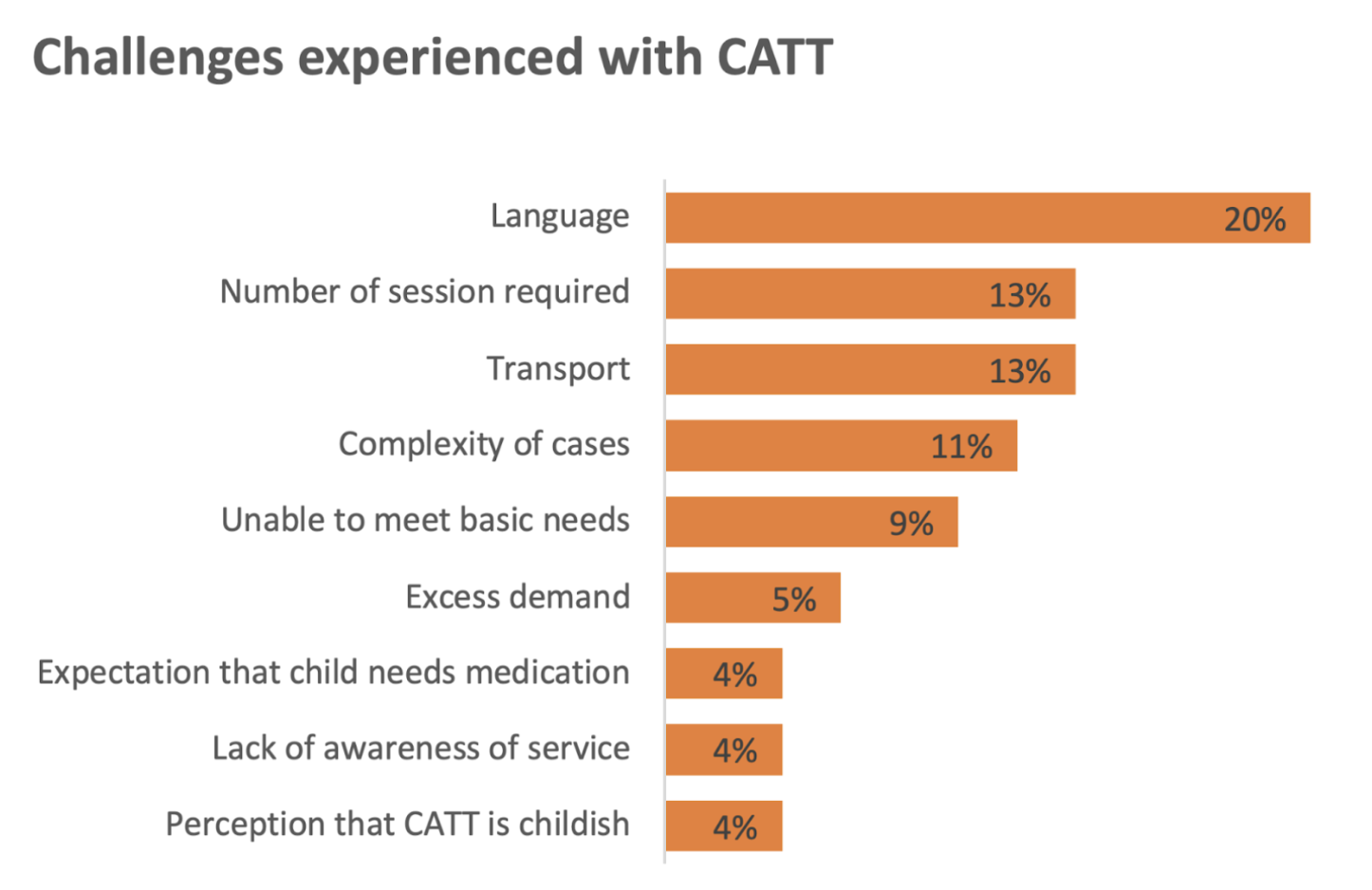

In a country with about 40 living languages and a large refugee population, it is perhaps not surprising that language was seen as one of the biggest challenges, mentioned almost equally by those working in referral hospitals and those in other settings. One counsellor pointed out that some local languages lacked words such as 'depression' and in some rural districts there was no one who could translate into English. Those working in refugee camps reported having to rely for translation on a child's relative or other refugees. Non-specialists and respondents working outside a hospital setting were more likely to mention the complexity of cases as well as the number of sessions required and challenges with transport.

A number of counsellors are volunteers who have to fit their CATT sessions in between regular duties. Apart from the counsellors employed by CRESS, most work singly without the benefit of a team. Others are employed on short-term contracts. Conditions of employment have a profound effect on their practice.

“Projects operate within a timeframe ... your project probably has a contract of six months, you are working with a child. Probably I got in contact with this child two months after the project has started, but I'm getting in touch with this particular child. The first steps of my CATT practice are taking about two, three weeks, to anchor the child into the next phase of treatment. And before I know it, the project is phasing before the child heals fully.” —Jackson M

“Today everyone is running. So many times they will give you about an hour and you have to divide that between your group and your individual sessions. If they give me about two days a week, I can say one day for a group and I get appointments for the second time I go to that school. But still, getting two hours in a week is very, very difficult because every teacher is trying to catch up with the syllabus. An hour would be a good time but you find that sometimes it's not complete. Children want to explain. So you find you've done 40 minutes and they are explaining to you and telling you, especially in the first session.” —Paul W

“They still consider me as a teacher. And that's why sometimes I become overwhelmed. I have to teach my lessons and children pass and get marks. ... Now the case comes in. A child is difficult in primary seven, they bring him to me; a child in primary four, they bring him to me. I'm in the middle of the lesson teaching. So what do I do? I receive this child. Another challenge I have, I don't have a place where you sit with the child and feel relaxed, where I can now set all these materials ... So I would wish entirely to specialise on handling, not teaching.”—Didas M

The less time counsellors are allocated for each case and the further they have to travel, the more likely they are to see the number of sessions required as a problem. Several reported that school administrators and parents would often cut the therapy short because they wanted a child back in class.

“Sometimes people complain that, you know, children are brought to them and then the next time they want to see the child, the child's been taken away and gone, you know, to another place or is put in school again and they won't give the time to it. But if they knew that for three days solidly, they would be there with the counsellor. That would be a good thing.”—James N

The cost of transport and distances covered present further challenges, particularly for counsellors working in rural areas or refugee settlements. Non-specialists and volunteers may also struggle to balance the needs of their CATT clients with professional and personal commitments.

“You are on duty as a general nurse, and then you have to spare time for these patients of CATT. And when you delay them, they get tired. They also go home. So you find it is not easy. You cannot work with the child without the family. So going to the families, it becomes expensive and it is time costing. So you find, we are missing out so many clients because of that ... And me as a health worker, I also don't have transport to go to their villages. And these are hill areas. You need time to walk and move to the mountains. So it becomes so difficult.”—Prima S

“West Nile comprises of around eight districts, so all are very far, very far ... If I'm to take motorbike, sometimes I can take something like five hours on the road. The roads are terrible. You have to plan your time as a counsellor. Because if you will be moving every week, or every two to three days, then your family needs you; you need to go to the field and dig for your family to survive. So balancing these things sometime becomes very tricky.”—Lulu E

The CATT protocol requires counsellors to conduct a needs assessment and ensure that basic needs are met, such as food, water, shelter, clothing and bedding. They work with systems around the child to build resilience and a sense of sustained well-being. In a country where a quarter of the population live below the poverty line and in large refugee settlements where people struggle for limited resources, this can present an almost insurmountable challenge.

“Here it's quite hard to get a safe place for a child. Sometimes even safe places like children's homes are not the safest.”—Paul W

“That is quite challenging, especially in some refugee camps. Because you might find that the food is not enough and you as a counsellor, you cannot provide the food. There is no safe water. You as a counsellor cannot provide the safe water. Maybe some children need mattresses. May be the camp authorities are not in a position to bring mattresses for these particular children or bring facilities. You might find that maybe there is no organization, which has the ability to provide those materials. So you find it still is quite lacking.”—Elias B

“Now if it comes to addressing basic needs of the children, then that becomes a challenge that we cannot really provide for these children”—Elias B

“Unfortunately, in the refugee camp sometime when you refer these children to those NGOs for their basic need, there's no feedback. There's nothing that can be done.”—Lulu E

Retention of CATT counsellors

In order to meet the selection criteria for CATT training, people must have a diploma or higher qualification, show evidence that they are working with children and, most importantly, have the right attitude and interest. Recruitment has accelerated and 14 outstanding counsellors have now become qualified to train others. However, as in other health service sectors, retention remains a problem. Only about half of the 160 trained counsellors are still practising.

“The drop out rate has been fairly high. For example, people who have been working in refugee camps have lost their jobs because some of them were laid off, especially during COVID times and maybe some agencies are not able to pay them. Then of course there are some who are no longer in active service. For example, in hospitals, either they have retired or they have been assigned other responsibilities. And therefore if they have been assigned other responsibilities, then they are no longer in contact with children. And therefore they cannot practise.”—Elias Byaruhanga, CATT co-ordinator

“We have done a lot of mental health training across the country, training them the basics, but I think the biggest problem is attitude, that even when many cadres are trained, they don't have the attitude to do mental health work. That is something you also find in people who have trained in CATT. Yes, they have trained with the certificate, but the attitude is not there.” —James N, Principal Clinical Psychologist, Butabika National Referral Hospital

The Ugandan Ministry of Health's 2017 policy guidelines for child and adolescent mental health mark a significant advance but implementation is patchy to say the least. Mental health remains a low priority when it comes to government spending, and child and adolescent mental health is still not properly integrated into healthcare.

“That (retention) has been a challenge, not only for CATT trained people, but generally mental health workers, because as a government policy, mental health is supposed to be integrated into general healthcare but its implementation has faced many challenges because we have, for example, a clinical officer at the general hospital, we are supposed to have a psychiatric nurse at the health centre, but when those people are posted there, you find they are not doing what they were posted to do. They are assigned other duties. You find out they're running HIV clinics, they are running immunisation - things they were not trained to do and you find they are not doing mental health services.” —Godfrey Zaari Rukundo, Head of Psychiatry at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital

It is not just government departments that prioritise physical over psychological well-being. In the non-government sector, mental health tends to be low on the list of priorities, representing only 0.3% of development assistance for health This affects the choice and structure of humanitarian projects.

“Most of the projects across the NGO world are designed by project officers or project managers. Now, project managers in our education system, largely study project management. They do not study sexual productive roles or domestic violence per se, psychiatric problems. No. So they can only design a project based on what the technicalities of a project are and it becomes very difficult for them to incorporate the components much needed for mental health.”—Jackson M

Memorable outcomes

Despite these difficulties, CATT counsellors are overwhelmingly positive about their role. In the questionnaire they were asked to describe any outcomes they were particularly proud of. Their responses shed light on the range of traumatic events that can blight children's lives and underline the value of their work.

“Helping an 11 year-old girl who had been raped multiple times by family members and neighbours. She developed strange behaviours, acting above her age with men, wandering from home, problem with sleep, nightmares, crying most of the time. But now she is well and performing well after eight sessions.”

“I successfully used CATT to treat four child soldiers/survivors in Khongo IDP camp and all of them responded so well and this has put a big smile on my face.”

“A boy with multiple trauma failed at school. His mother had left home and left him with a grandparent who died while the boy was watching so he is now head of the family. He was wandering and could not stay at home but is now in school and doing well at home.”

“A child who was involved in a traffic accident. I saw him work through his trauma and improving, able to go back to school and now at university.”

Conclusions and areas for development

When so many children and young people in Uganda are exposed to traumatic events which can blight their lives, there is an urgent need for effective and accessible models of care. As this research shows, CATT has become an important tool for mental health professionals and others working with children. The number of counsellors and trainers has steadily increased and respondents to the questionnaire are consistently positive about the therapy, emphasising its child-centred approach and use of non-verbal narrative based on play. When asked how many children responded well to CATT - “many, some or few” - over half the respondents said "many". The overwhelming majority believe that it has a positive impact on the child's family and some think it benefits the community at large by increasing an understanding of mental health. During interviews, several counsellors remarked on the improvement CATT training had had on their practice.

Although they are overwhelmingly positive about the CATT protocol and the therapeutic technique itself, many face challenges when using it on the ground, such as the need to find reliable translators, the cost of transport and the number of sessions needed to complete a case.

Some counsellors say they have not received as many referrals as they would wish and call for more public awareness campaigns, but others report being overwhelmed by cases. Overload is a particular problem for those working in refugee communities, where levels of post-traumatic stress are exceptionally high. These environments may also lack food, clean water and shelter, making it almost impossible for counsellors to meet a child's basic needs as the CATT protocol requires. One of those interviewed said that it was sometimes hard even to ensure a child's safety.

Many of the challenges highlighted in the research are structural, relating to funding priorities and conditions of employment and are possibly a contributing factor to the drop-out rate among trained counsellors, which stands at about half. Child and adolescent mental health is not yet fully integrated into medical services so practitioners have to divert to another type of medicine if they want to gain promotion. Counsellors with other professional responsibilities such as general nursing or teaching may struggle to find time for voluntary work. Time may also be a problem for counsellors employed by humanitarian organisations on short term contracts*. In addition, non specialist CATT counsellors may lack the supervision and peer support needed to improve practice and prevent burn-out. They are also more likely to face difficulties when treating children with complex trauma.

There are lessons to be learned from the two examples of working practice that are highlighted in this report. Outcomes recorded by the CRESS team in Northern Uganda and case notes from the Bishop Asil Counselling, Rehabilitation and Community Centre in Lira demonstrate a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms following CATT, a success reinforced by the testimony of four children and their carers who were interviewed for this research.

There are distinguishing features which help to make these results outstanding. Unlike most practitioners who took part in this research, those employed by CRESS work in a team, supporting each other and reporting to a co-ordinator who monitors their results and feeds them back to the charity. Although they are volunteers, they receive a modest remuneration and are provided with bicycles and mobile phones. As refugees themselves, they are thoroughly embedded in the community they serve.

As director of Bishop Asili Centre and a respected member of a religious community, Sister Florence is better placed than some other counsellors to ensure that a child's basic needs are met. In Lira she can house children at the Centre and in Kisubi she has a network of foster parents to call on. The four children interviewed no longer showed symptoms of PTSD and their carers confirmed that they were able to play and go to school. Moreover, they were enjoying opportunities such as education and sport that would otherwise not have been available to them.

Areas for development

Many of the challenges facing CATT counsellors could be overcome if the Government of Uganda implemented its own policy guidelines on child and adolescent mental health. As a charity, ACT International is responsible for training counsellors who then go on to train others but has no responsibility for working conditions. It may be useful, however, to list areas of improvement that arise from the evidence given by counsellors in the course of this research.

- CAMHS (with CATT) needs to be integrated into health system - with a recognised promotional ladder.

- Non-specialist counsellors should be given time and space for their CATT work.

- The number of counsellors needs to be increased to make existing workloads more manageable.

- All counsellors should receive supervision and take part in peer group counselling to avoid drop -out and emotional fatigue.

- Counsellors should monitor and report on outcomes and this information should be held centrally.

- Counsellors need further training about complex health needs.

- Volunteers need remuneration and help with costs.

- Partner organisations / funders are needed who can help provide children's basic needs, particularly in poor rural areas and refugee settlements.

- More translators are needed.

- Transport costs should be met.

- Counsellors should be encouraged to increase public awareness of mental health issues through media outlets and forms of public engagement.